Creative Commons and digital projects

Tuesday, May 27th, 2008 | karin dalziel

When I submitted my ideas for THAT camp, I listed Free Culture (Creative Commons in particular) and localization of the Internet as my topics. I think the localization thing is covered by several proposed topics here, and I’m anxious to sit in on all of them (realizing, of course, that I will likely have some conflicts).

As for Creative Commons, I’m not sure how much this crowd a) knows about Creative Commons already and b) wants to know. I think most academics- especially those involved with a digital projects- get pretty tired of copyright talk. Though it is necessary, it’s not the most fun topic. For most, anyway.

Creative Commons is an attempt at self regulation to clean up the copyright mess. As an (amateur) artist, I use CC to license my own work, and I am fascinated by how it has worked out for authors like Cory Doctorow. I worry, though, that the model is not sustainable- especially in the case of incompatible licenses. As an individual creator, deciding how to license my own work is hard enough, but when you take a digital project, mix in old and new materials plus original scholarship, you have the recipe for a huge mess. I have more questions than answers, including:

- How should digital projects be licensed? Should the scholar retain full copyright and dole out permission as requested? Or should he or she try and choose a license that allows for use from the beginning?

- How can creators of digital projects make users aware of copyright without hitting them over the head with it? This is especially a problem with projects that contain some public domain materials and some that are still under copyright.

- What kind of support do institutions give for alternative licenses? I know many universities require copyright to the university by default.

- How can we build copyright decision making into programs like Omeka. I think Flickr does an OK job of this, they allow users to select a CC license when uploading photos, and restraining search to CC only materials. But I think it could be done even better.

What relates most to THAT Camp is that last point- because right now, it is really hard to consistently find, use and keep track of Creative Commons work. If people are interested, I could give a brief overview of various licenses and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of creative commons and other licenses.

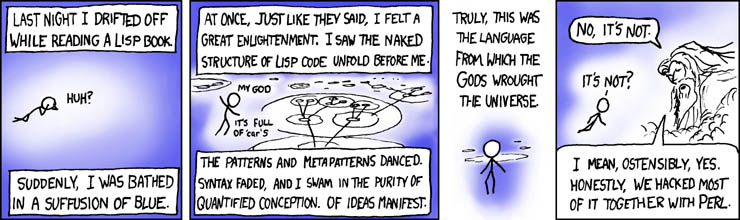

From XKCD, a CC licensed webcomic.